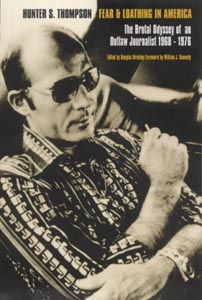

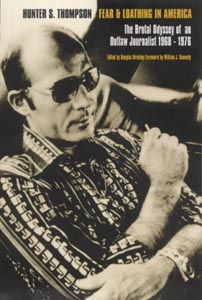

Writer Hunter S. Thompson Kills Himself

Hunter S. Thompson, the hard-living writer who inserted himself into his accounts of America's underbelly and popularized a first-person form of journalism in books such as "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" and "Hell's Angels," has committed suicide. News story here.

What follows is a copy of a tribute feature at Pitchfork:

To my knowledge, Hunter S. Thompson never wrote a record review. His famous involvement with Rolling Stone was incidental to its focus on music, and due merely to Jann Wenner's willingness to publish lengthy screeds and pay both relatively well and on time. But, despite some people's opinion, we at Pitchfork are all writers, and as ones prone to the occasional experimental flight and its frequent partner self-indulgence, we live in the shadow of Hunter just as much as those of Lester or Greil.

Predictably, most body-still-warm retrospectives on Thompson's life have been drawn to wrongheaded discussions of drug use and general debauchery rather than his influence on the writing world. But it's hard to get to self-righteous about this treatment-- by the time of his death, HST had long been something of a caricature, both literally, in Doonesbury, and figuratively, through his increasingly bizarre rants about paranoia and football gambling published on ESPN's Page 2. Whether drawn by Trudeau or Steadman, Thompson is cursed to be forever portrayed with cartoon circles orbiting his Panama hat, nothing but a Halloween costume or a t-shirt.

Few seem to have noticed that the absurdly exaggerated drug use of Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas is given a portrayal that is far from enticing, note-perfectly enacted by Terry Gilliam's film of the book. To Thompson, his persona's ingestion of drugs wasn't a celebration of counterculture mind exploration, but a desperate self-inoculation against the increasingly diseased American atmosphere closing in on all sides. Fear & Loathing didn't earn its place in American literature as a celebration of pharmaceutical joyriding, but rather as an obituary for the delusional promises of the 1960s--it's a literary Altamont.

Also seemingly misunderstood are Thompson's politics, often summed up merely as being anti-Nixon and, as such, implicitly leftist. In truth, HST's views ran much closer to libertarian recluse, with his main political issue being the right to own very large guns, and his lunatic run for sheriff on the Freak Power ticket mostly a reaction to ski resorts moving in on his Colorado compound. If Thompson had a political agenda, it was primarily against the invasion of government into private life, and recent times had only given him renewed reason to trot out the phrase most often associated with his work.

But the truly lasting impact of Hunter S. Thompson's life will forever be his subversion of traditional journalistic technique, injecting pure subjectivity into the sometimes pious, self-deceiving arm of reporting. Realizing that it was impossible to completely subvert one's personality towards the end of objectively stating facts, Thompson took things to the opposite extreme, placing himself in the scene whenever possible and running off on fantastical tangents when reality got too dry. He knew riding with and subsequently getting beat down by the Hell's Angels would get the story better than interviews and microfiche, knew that the Kentucky Derby's snobbish depravity was better covered drunk and betting profligately than from the detachment of the press box.

Yet this innovation isn't merely manifest today in the pretensions of silly indie rock reviewers. In a news world overrun by pundits drunk on their sense of infallibility, the needle of Gonzo journalism is all the more necessary, which is probably why "The Daily Show" out-reports the 24-hour infotainment factories with a scarily high frequency. Literature meanwhile continues to go through cycles of fourth-wall demolition, most recently with the rise and fall of hyper-reflective memoirs, while documentary films start to free themselves from the restrictions of cold, emotionless observation and embrace subjectivity with the same rush HST delivered 30 years ago.

While Thompson's self-inflicted death immediately felt more horrible than a natural-cause variety exit, the waiting period of a slow deadline has brought his choice into sharper focus, almost seeming like a logical final act to his career. Anyone who has seen recent footage of the man knows his health was grim at best, and it's only fitting that Thompson would chose to flex his subjectivity one last time regarding the timing and nature of his own demise. So let's not dwell on the ugly details of his death, nor the cultural distortion of his personality into a grinning Johnny Depp gripping a cigarette holder between his teeth and popping mescaline. Instead, let's dwell on the Jill Krementz's photo on the cover of his second letters collection: sitting in a car, wearing an ugly shirt, thinning hair, and a contemplative expression while, in his mind, he redrafts the rules of journalism.

What follows is a copy of a tribute feature at Pitchfork:

To my knowledge, Hunter S. Thompson never wrote a record review. His famous involvement with Rolling Stone was incidental to its focus on music, and due merely to Jann Wenner's willingness to publish lengthy screeds and pay both relatively well and on time. But, despite some people's opinion, we at Pitchfork are all writers, and as ones prone to the occasional experimental flight and its frequent partner self-indulgence, we live in the shadow of Hunter just as much as those of Lester or Greil.

Predictably, most body-still-warm retrospectives on Thompson's life have been drawn to wrongheaded discussions of drug use and general debauchery rather than his influence on the writing world. But it's hard to get to self-righteous about this treatment-- by the time of his death, HST had long been something of a caricature, both literally, in Doonesbury, and figuratively, through his increasingly bizarre rants about paranoia and football gambling published on ESPN's Page 2. Whether drawn by Trudeau or Steadman, Thompson is cursed to be forever portrayed with cartoon circles orbiting his Panama hat, nothing but a Halloween costume or a t-shirt.

Few seem to have noticed that the absurdly exaggerated drug use of Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas is given a portrayal that is far from enticing, note-perfectly enacted by Terry Gilliam's film of the book. To Thompson, his persona's ingestion of drugs wasn't a celebration of counterculture mind exploration, but a desperate self-inoculation against the increasingly diseased American atmosphere closing in on all sides. Fear & Loathing didn't earn its place in American literature as a celebration of pharmaceutical joyriding, but rather as an obituary for the delusional promises of the 1960s--it's a literary Altamont.

Also seemingly misunderstood are Thompson's politics, often summed up merely as being anti-Nixon and, as such, implicitly leftist. In truth, HST's views ran much closer to libertarian recluse, with his main political issue being the right to own very large guns, and his lunatic run for sheriff on the Freak Power ticket mostly a reaction to ski resorts moving in on his Colorado compound. If Thompson had a political agenda, it was primarily against the invasion of government into private life, and recent times had only given him renewed reason to trot out the phrase most often associated with his work.

But the truly lasting impact of Hunter S. Thompson's life will forever be his subversion of traditional journalistic technique, injecting pure subjectivity into the sometimes pious, self-deceiving arm of reporting. Realizing that it was impossible to completely subvert one's personality towards the end of objectively stating facts, Thompson took things to the opposite extreme, placing himself in the scene whenever possible and running off on fantastical tangents when reality got too dry. He knew riding with and subsequently getting beat down by the Hell's Angels would get the story better than interviews and microfiche, knew that the Kentucky Derby's snobbish depravity was better covered drunk and betting profligately than from the detachment of the press box.

Yet this innovation isn't merely manifest today in the pretensions of silly indie rock reviewers. In a news world overrun by pundits drunk on their sense of infallibility, the needle of Gonzo journalism is all the more necessary, which is probably why "The Daily Show" out-reports the 24-hour infotainment factories with a scarily high frequency. Literature meanwhile continues to go through cycles of fourth-wall demolition, most recently with the rise and fall of hyper-reflective memoirs, while documentary films start to free themselves from the restrictions of cold, emotionless observation and embrace subjectivity with the same rush HST delivered 30 years ago.

While Thompson's self-inflicted death immediately felt more horrible than a natural-cause variety exit, the waiting period of a slow deadline has brought his choice into sharper focus, almost seeming like a logical final act to his career. Anyone who has seen recent footage of the man knows his health was grim at best, and it's only fitting that Thompson would chose to flex his subjectivity one last time regarding the timing and nature of his own demise. So let's not dwell on the ugly details of his death, nor the cultural distortion of his personality into a grinning Johnny Depp gripping a cigarette holder between his teeth and popping mescaline. Instead, let's dwell on the Jill Krementz's photo on the cover of his second letters collection: sitting in a car, wearing an ugly shirt, thinning hair, and a contemplative expression while, in his mind, he redrafts the rules of journalism.